Telling the story of Sir Terence Conran, who passed away on September 12, is a bit like telling the story of the West over the last 70 years, with the evolution of habits and the spread of design in everyday life. On the one hand, Terence Conran’s life represents the story of many people in the aftermath of World War II, on the other hand, it is the story of a special person, who gave a great contribution to design culture, skillfully mixing commercial and cultural activities.

Born in Kingston upon Thames, one of London’s Royal Boroughs, in the Thirties, Terence Conran worked with design and food throughout his life, mixing them in the creation of concept stores, the management of restaurants and the active promotion of culture. He opened stores and restaurants in the UK, New York, France, Japan, Korea (and in Italy, where unfortunately Habitat had a very short life – now it has come back, but with a different owner). He also wrote books, founded museums and in 1983 was appointed “Knight Bachelor”.

In the pictures, the set-up of Habitat Milano in 1997, designed by Ferruccio Laviani (photo courtesy Ferruccio Laviani)

Designing life

His adventure began with a furniture store in Notting Hill and a restaurant, in the early Fifties. The Conran Design Group, the first integrated design studio, dates back to 1956. Here, furniture and interiors were designed and thought about how to sell them. With the group, Terence Conran began producing flat-pack furniture, and, in 1964, opened the first Habitat store, on Fulham Road. In 1966, Habitat opened its second store, on Tottenham Court Road, and in 1973 the first Conran Shop replaced Habitat on Fulham Road. Today, The Conran Shop is still near to the original location: in 1987, it moved to the Michelin building (Bibendum), on the corner of Fulham Road and Sloane Avenue, where it is still located today.

These addresses are not accidental. On the contrary, they are the ones that marked the beginning of the transformation of the area that, over time, has led to today’s Brompton Cross Quarter, which hosts the Brompton Design District, during the London Design Festival. Because one of Terence Conran’s merits, among others, was a talent for finding spaces and places to revitalize.

In addition to design stores, Terence Conran developed a passion for food and started investing in Covent Garden. In 1971 he opened the Neal Street Restaurant, with the menu designed by David Hockney. Among other things, Conran was also the first to serve espresso coffee from a coffee machine in his restaurants.

The Design Museum

However, Terence Conran had not only a commercial spirit, or perhaps he understood the commercial potential in culture, so in 1980, with the Conran Foundation, he started the Boilerhouse project in the basement of the Victoria & Albert Museum. Within a few years, Boilerhouse organized exhibitions on Kenneth Grange, Issey Miyake, and Dieter Rams, as well as seminars and meetings. Its success was so big that in 1989 it metamorphosed into the Design Museum, in an old converted warehouse. Since 2016 the Design Museum has had a new home, designed by OMA, Allies and Morrison, and John Pawson.

Below, the Design Museum inaugurated in 2016, in a building designed by OMA, Allies + Morrison, and John Pawson

Sir Terence Conran and the USA

In 1999, The Conran Shop arrived in New York. The first Conran Shop was on the 59th street, under the Queensboro Bridge, a glass pavilion in a beautiful location, with a façade overlooking the East River.

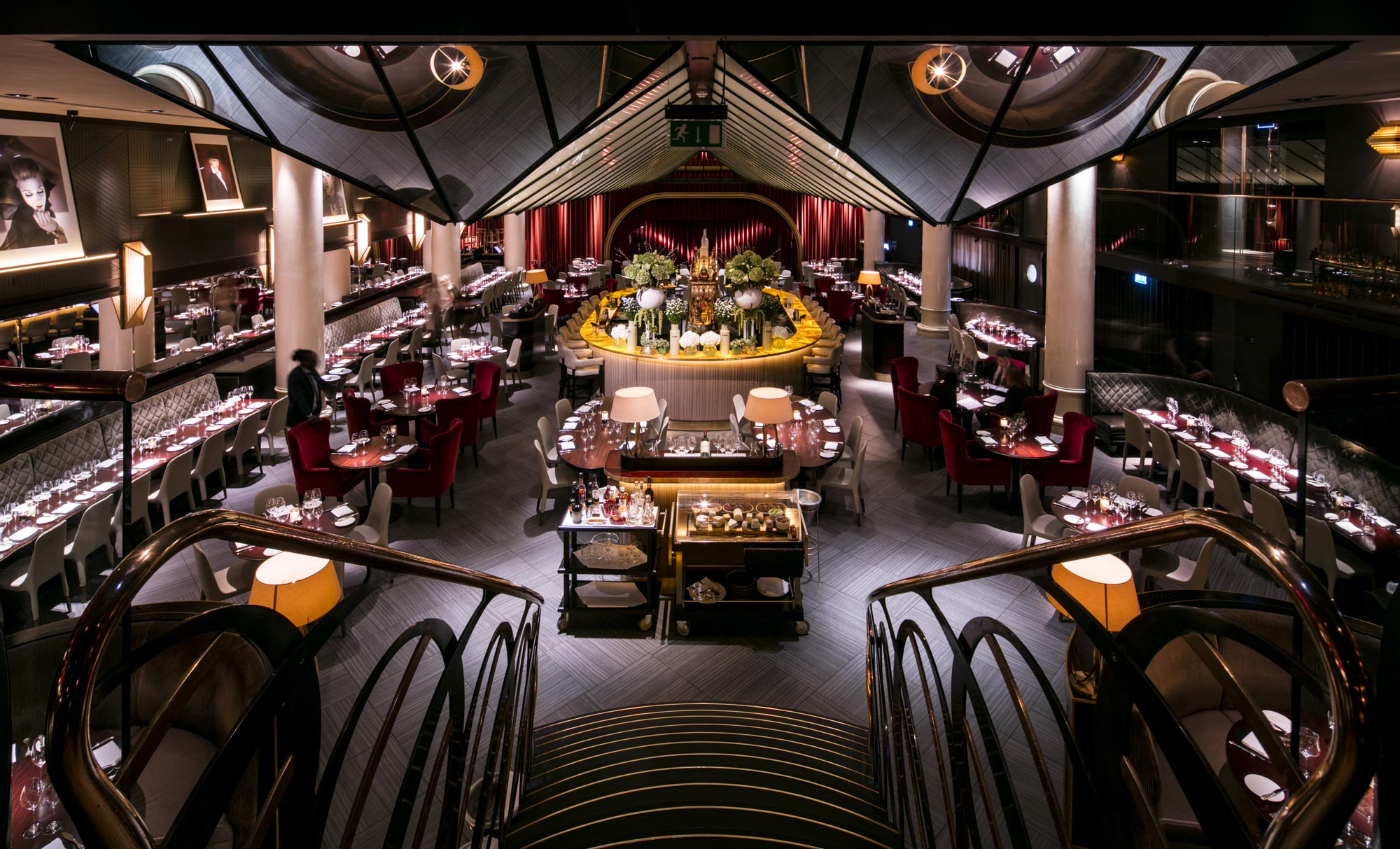

In the meanwhile, the passion for food was growing, and what’s better than a good restaurant in a beautiful place? Said and done, he relaunched Guastavino’s, in the spaces of the Queensboro Bridge Market, next to the Conran Shop. The building that housed the Queensboro Bridge Market and Guastavino’s was spectacular, a sort of contemporary cathedral. Guastavino’s was not the only restaurant relaunched by Terence Conran. In 2003, he also contributed to the rebirth of Quaglino’s in London. In more recent times, the Bibendum has been included in the Michelin Guide.

Considering stores, production, restaurants, museums, Terence Conran’s contribution to the worldwide spread of design was really remarkable. Probably thanks to the enthusiasm of the post-war recovery and the consequent economic development, new consumer habits and new products were entering British homes.

And enlightened entrepreneurs like Conran were ready to take advantage of that favorable moment to start businesses combining trade and culture. This is the long-standing debate among detractors and promoters of the “democratization of design”. Of course, perhaps Habitat’s design did not have the research content that characterized high-end projects, but it appealed to an undoubtedly larger segment of the population, thanks to new distribution concepts.

Perhaps Terence Conran had the quite rare ability to combining commercial activities and culture, offering wider segments of the population the opportunity to improve their knowledge of design. [Txt Roberta Mutti]